Notes on successfully migrating 4900 bug reports from Bugzilla to GitHub issues

Prelude

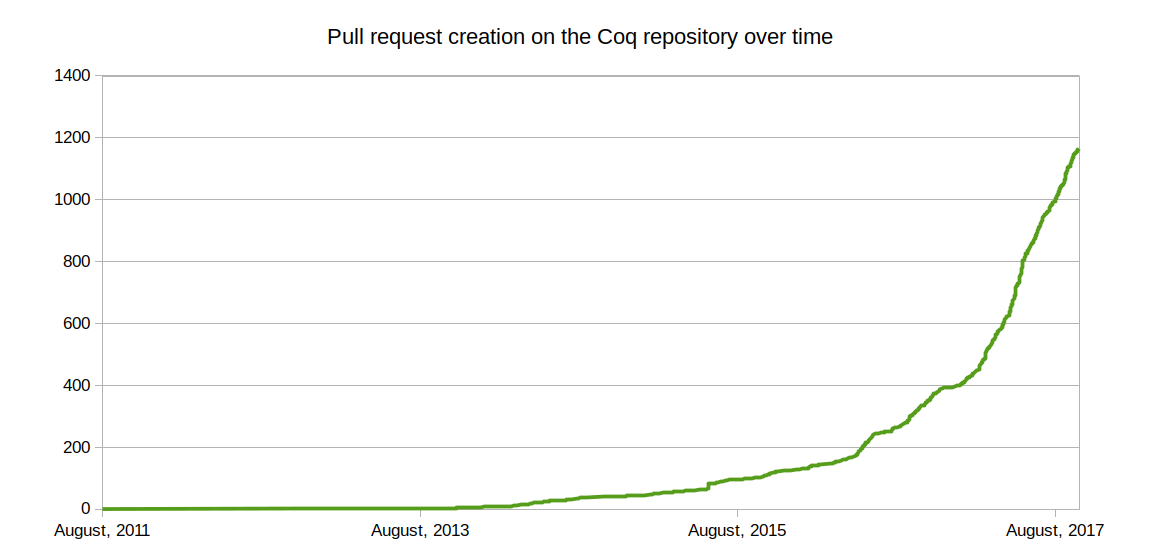

I started contributing to Coq in 2015. This year, the Coq development team was organizing the first Coding Sprint (later renamed into the Coq Implementors Workshop) and was accepting pull requests on the GitHub repository to get patches from external contributors1. Back in these days, almost none of the development was carried out through pull requests (I opened PR #68). Things have changed dramatically since then.

Pull requests are now used routinely to review other developers’ patches before integrating them; continuous integration was introduced to automatically test whether a proposed change breaks a number of tracked external developments (plugins and libraries)2. These new processes have brought much stability to the software at the price of a reasonably small overhead. They have also demonstrated to be an excellent tool for sharing knowledge.

Meanwhile, bugs continued to be reported on Bugzilla, the bug tracker that was used since July 2007 (after a first migration from JitterBug). Bugzilla suffered from many drawbacks that were made all the more apparent when comparing to the much nicer experience we were having in pull request discussions on GitHub.

Simply setting e-mail notifications for new bug reports was a hard task: we had the mailing list coq-bugs-redist@lists.gforge.inria.fr which was connected to a Bugzilla account that was put in cc of all new bug reports. But to subscribe to this mailing list, you had to get moderator approval and, for some time, no one was administrating this mailing list anymore3.

More importantly, the lack of edition features, the difficulty to search an issue, the loading times, the intimidating UI had a (non-quantified but probably) significant impact on the developers, who tended to prefer slightly off-topic discussions and digressions in a pull request thread, rather than discussing each specific issue in a separate thread on Bugzilla.

In April 2017, I opened a wiki page to discuss the possible alternatives. Having a strong preference for gathering all our tools on GitHub, I documented this one (and no one really documented any other alternative, even if they existed).

In August, the Coq website was down for more than a week because of an over-reaction of the IT services to an alleged hacking of the bug tracker (in fact just a spam). This was a good opportunity to discuss once more a migration to GitHub issues (with hosting less dynamic, subject-to-attack, content as a nice benefit).

While I was initially proposing a transition during which we would be using both bug trackers in parallel, the need to keep bug numbers as much as possible was expressed and a script was found4 which was designed for that purpose.

The migration script

The migration script that was found is a Python script5 which takes an export from Bugzilla to XML as input and uses the GitHub API to create new issues for every bug reports. It inserts first the bug reports whose number it can keep6 and only when this is done it inserts bug reports that need to be renumbered.

Because issue numbers are attributed by GitHub at creation time and are not chosen by the issue author, it is not possible to skip some non-existent bug number. That’s why the script contained an initial check that the input bug numbers are contiguous. This was not the case for the Coq Bugzilla: many bugs had been deleted, especially in the early years. Thus, the first modification that I did to this script was to use postponed bug reports to fill the holes (missing bug numbers) to recreate continuity in the result. This worked because the number of pull requests was already higher than the number of holes.

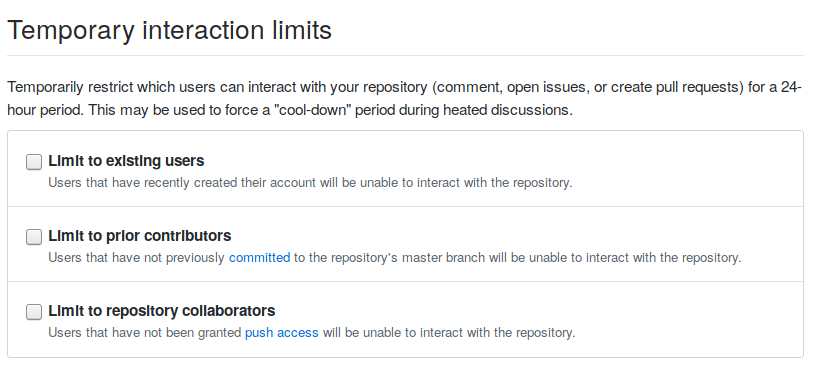

To increase the predictability of new issue numbers, it was important that no issue or pull request be opened during the few hours that the migration took to complete. This was achieved thanks to the “cool-down” feature that GitHub provides.

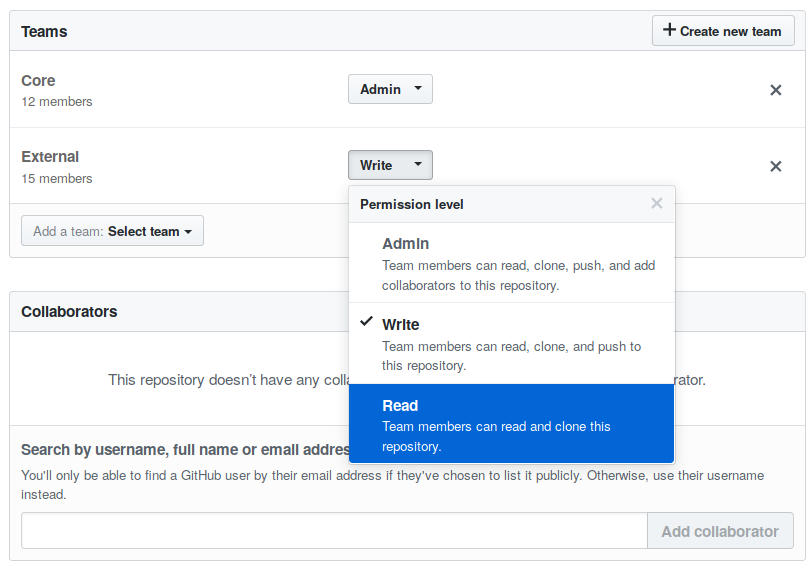

We wanted to limit interaction permissions as much as possible during the migration, but removing contributors also meant losing the ability to assign issues to them. The solution that was found was to add all the people who had bug reports assigned to them to the External team of the Coq organization, then temporarily restrict the permissions of this team to “Read” (basically the same thing as anyone else given that this is a public repository).

Another critical issue with the script was that the GitHub API was limiting issue creation to 300, after what it refused any new posting for the next 30 minutes (not just through the API by the way, during my tests I was also prevented from manually posting comments during this delay). While I initially implemented a wait-period, this limitation was going to make the migration unbearably long. Fortunately, after reaching out to GitHub support, they explained that this limitation was imposed on any interaction that emitted notifications but that they also provided a beta API specifically dedicated to issue import that had many notable advantages, one of them being that new issues created through this API did not emit notifications, and thus were not submitted to the same rate limits.

There are many more advantages to this API: you can create at once an issue and many comments, set creation dates for each of them, assign someone, set a milestone and some labels, etc. Adapting the script to this API was easy: the main difference is that the API is asynchronous. To ensure that issue numbers are predictable, you must make it synchronous by sending GET requests to check whether an issue has been created before sending the next one. On the advice of GitHub support, I implemented a back-off approach: first wait one second before sending the GET request, if still pending wait for twice that time before sending another request, if still pending wait for twice the previous time, etc. The one-second delay meant that we could not import more than 3600 issues per hour in theory (in practice the migration almost took four hours, which indicates that many times it took more than one second to import an issue; I did not collect this information, unfortunately).

On the other hand, the API still has some limitations: you can’t recreate the

complete history of closing/re-opening and assignments, the labels and the

assignees are put at issue import time, whereas you can set the

closing date. I regret not having set the updated_at field: I did not see

what purpose it served: in fact it is useful when you sort issues by “Recently

updated” (then GitHub displays the date of the last update).

This API does not allow you to choose the author of issues / comments either and requires API requests to be authenticated with a repository administrator API token. That’s why our bot account @coqbot appears as the author of all imported issues and comments.

Some other improvements of the script included saving a trace of imported bug reports with the Bugzilla / GitHub ID correspondence, and using this to safely recover from possible crashes, fixing most references to other bug reports, and some very Coq-specific stuff like not displaying comment authors for the first 1657 comments because these were imported from JitterBug to Bugzilla ten years ago and the migration attributed all the comments in a given bug report to the initial reporter.

The resulting script is, I believe, largely improved over the original one but also not as generic. If you wish to use it for your own migration, feel free to do so and don’t forget to remove the Coq-specific material first. If you want to share the result, especially if it is more generic, and thus a better basis for future users, I will be happy to add the link from this post.

Epilogue

The migration was formally approved at the Coq Working Group on Oct 3-4th, 2017, and was conducted right after the 8.7.0 release, on the morning of October 18th. It was preceded by a series of e-mails to announce it and the fact that both bug trackers (the old and the new one) would be read-only for the duration of the migration.

All the bugs with a number below 1154 had to be renumbered, you can find a nice correspondence table with a search bar here. All the other bugs kept their number.

While the migration went smoothly, only time will tell how effective the change was on the development organization. I plan to fiddle with the GitHub API some more to get interesting statistics of issue creation before and after the migration (with the cool advantage that dates have been preserved for bug reports from before the migration), how long it takes to solve a bug on average, the growth of unsolved issues, etc. If you know of some services or scripts that already provides such statistics, I would be happy to know about them.

In other news, Pierre Letouzey has migrated the Coq wiki to GitHub as well :) which means that the Coq website is fully static now.

Updates

- Pierre has reused the correspondence table to redirect previous Bugzilla URLs to new GitHub ones. For instance, https://coq.inria.fr/bugs/show_bug.cgi?id=2 now redirects to https://github.com/coq/coq/issues/1156 and https://coq.inria.fr/bugs/show_bug.cgi?id=1153 now redirects to https://github.com/coq/coq/issues/5970.

- Erik Martin-Dorel has adapted the script to the migration of issues from a GitHub repository to another one and has used it successfully to migrate the 101 issues from https://github.com/psteckler/ProofGeneral to https://github.com/ProofGeneral/PG. The new script is available at https://github.com/erikmd/github-issues-import-api-tools.

-

As can be seen on the graphic, pull requests started being opened much before (in August 2011) but the Coding Sprint marked (to my knowledge) the time when the Coq development team started to encourage contributors to open them. ↩

-

See the documentation of the continuous integration here: https://github.com/coq/coq/tree/master/dev/ci#continuous-integration-for-the-coq-proof-assistant ↩

-

In this thread, we discover that the administrator of the mailing list was someone who had left the development team for several years. ↩

-

By Guillaume Melquiond, https://sympa.inria.fr/sympa/arc/coqdev/2017-08/msg00042.html ↩

-

It is now available on the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/berestovskyy/bugzilla2github. It has received a number of improvements since then. ↩

-

On GitHub, issue reports and pull requests share a common set of identifiers. Given that about 1100 pull requests were opened on the Coq GitHub repository before the start of the migration, that was as many numbers that couldn’t be used for issue reports. ↩